My grandmother Alice Elizabeth Manson was born on Dec. 26, 1898, in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Her father, Frederick E. Manson, originally from Searsmont, Maine, had moved with his bride, Alma Millay from Bowdoinham, Maine, to Williamsport, Pennsylvania to take a job as the Managing Editor of Grit, an agricultural newspaper catering to an audience of farmers and homesteaders. (Grit: “rural American know-how.”)

and their mother, Alma Millay Manson, center

My grandmother had one full sibling, Frances Viola. Their mother, Alma, was of fragile health and died in 1907 after a series of strokes, when my grandmother was nine. Frederic E. later married Catherine Rentz and, together, they had three daughters: Helen, Catherine Jane, and Ann Pattee, and so there was a household of five daughters.

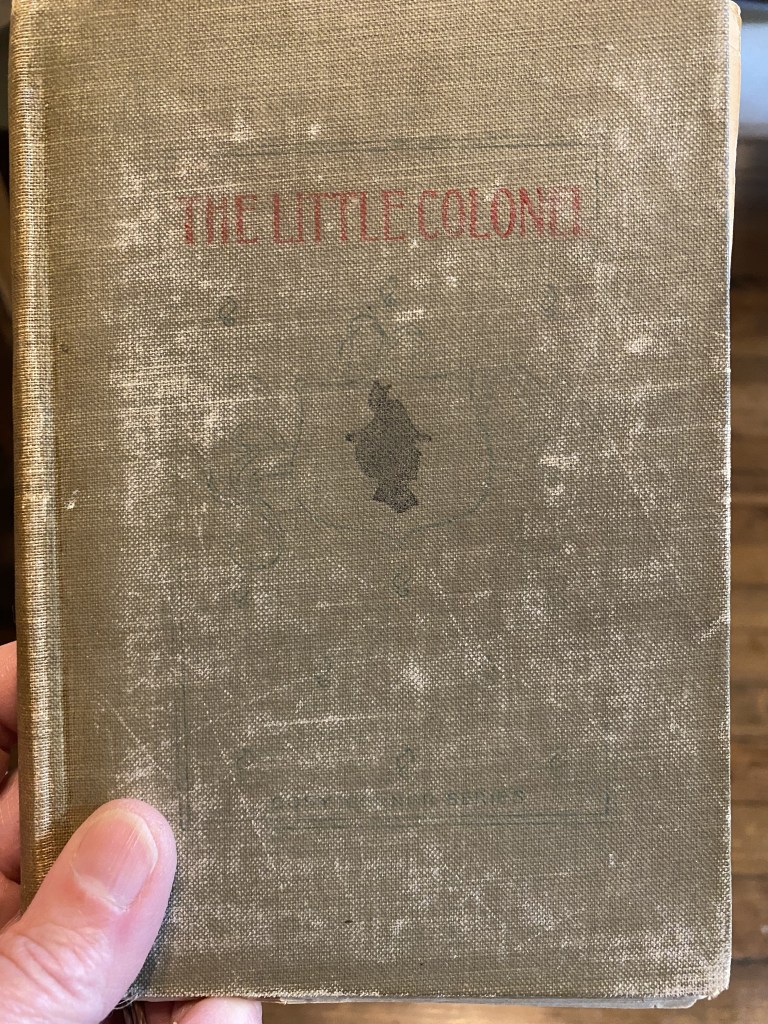

Among the toys and games of these five young girls was a series of books that, 60 years later, came into my possession. The Little Colonel was a series of books by Annie Fellows Johnston that chronicled the life and times of a young girl in Kentucky whose grandfather, Colonel Lloyd, was a plantation owner and Civil war veteran, having lost “his only son and his strong right arm to the Southern cause… thirty years earlier.” (The Little Colonel, pg. 6, LC Page and Company, Boston, 1906). This places the setting of the early Little Colonel volumes at about 1895. The series- 15 books in all- was published between 1896-1914. Also included with the series was a book of paper dolls so readers could act out some of their favorite scenes and continue the story of the various characters in the books. I loved reading these stories in the musty, yellowed volumes: Some of my favorite titles were “The Little Colonel’s House Party” (in which she gets to have a group of friends stay with her for weeks on end at the plantation), “The Little Colonel’s Holidays,” and “The Little Colonel at Boarding School.” So popular were these stories that they were turned in to a movie starring Shirley Temple (as the Little Colonel, of course,) in 1935.

Among the characters in The Little Colonel were a black housekeeper, Mom Beck, who lived with the Little Colonel and her mother, the (Sr.) Colonel’s “body-servant” Walker, who lived on the plantation, and May Lilly, a young servant child, about the same age as the Little Colonel.

The books are a period piece that describe life in the time of Post-Reconstruction South.

On a recent trip to Gettysburg, I was reminded that the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 only applied to slaves in Confederate states. (The irony that I am writing this essay on Juneteenth, the day in which we commemorate the news of emancipation reaching Texas in 1865 is not lost on me…). The enslaved who lived in the border states of New Jersey, Kentucky (the setting of The Little Colonel) and Delaware had to wait for the passing of the 13th Amendment in December 1865 to win their freedom. And even then, some People of Color were still subjected to involuntary labor under the Black Codes which compelled them to work for lesser- or no- wages.

I don’t know what the situation was for Colonel Lloyd’s help on the plantation “Locust,” or for Mom Beck, the loving nanny and housekeeper who cared for the Little Colonel in her house in the village; the relationships between the white folk and their black help seemed courteous and respectful in the books, but friends, any writing that normalizes a stereotype of the “big black mammy” (Mom Beck), or the little black playmate (May Lilly) as a “plantation urchin” in bare feet and an outgrown frock, or a deferential manservant (Walker), or that uses the term “darkies” repeatedly and mentions “low -flung n—–s” is not good with me. Not good at all.

A few weeks ago, I burned an old broken paint box that belonged to my father in the backyard oil drum that we use as a burning bin. My father died when I was a toddler and I’d been holding on to some artifacts of his that gave me a thin thread of connection. But in cleaning out my basement and engaging a summer of “downsizing,” I decided that this broken box (a wooden briefcase of sorts) was beyond repair and that it had to go. I gave it a proper ending by burning it, rather than adding it to the week’s garbage bin along with the coffee grounds, banana peels and chicken bones. It made me feel good- lighter- to be free of this item that I’ve been dragging around with me for the past few decades from house to house… but also very sad.

I think that I’m going to take my Little Colonel volumes to the bin and destroy them in the same manner.

Book burning- book banning, for sure- has been a big topic of late as school districts and municipal leadership around our country are debating what is and is not appropriate material for our children to read. Books featuring families with same-gendered parents, or children who are questioning their sexual identity, or stories of transgendered individuals are being pulled from library shelves for their “inappropriate” content. I consider The Little Colonel, period piece though it may be, to be inappropriate. So, why is it alright to destroy this collection of writing while arguing against the removal of other writing? In my mind, it is clear: the literature that I want to have available to our young readers should be inclusive, loving, respecting the dignity of all people, and not portraying one strata of humankind as better than another. The Little Colonel, even with its docile portrayal of black servitude, fails that test. To the bin it goes.

I do not want my granddaughters- or grandsons- to read The Little Colonel. I do not want them to see this division of humankind into strata, this cartoon of benign servitude drawn across racial lines to seem acceptable. I know that there are those who could argue that sheltering children against the reality of our society in which social strata is alive and well is ridiculous, but the not-so-subtle visual that all of the help in The Little Colonel are People of Color and all of the “employers” are rich white folk is not what I want to add to my grandchildren’s formation. The subjugation of People of Color is not something that I want to promote in the handing down of antique literature. Paper dolls are, of course, a charming old idea, but my grandson seems to be making out fine with his action figures. And, on inspection, as I laid out the paper dolls on the dining room table last night for one last look, I discovered that May Lilly had only the knickers she was dressed in. Everyone else had many outfits. I guess May Lilly was supposed to wear hand-me-downs.

Juneteenth, 2023.

Audrey, rather than burning this collection, please donate it to a research institution (a university, a historical society, eg. NY Historical Society, Library of Congress). Just as all the scraps of writing that didn’t make it into the New Testament canon help flesh out the background of the N.T., this collection may help flesh out the cultural history of the U.S.A. Researchers of childrens’ literature would be interested in these. Try to find the titles in the little colonel that are listed in WorldCat. I could try to find out more, if you like. with warm regards, Viola

LikeLike

Wow. A lot to think about here. The thought of burning a book- just about any book – makes me gasp. And I cling to objects and historical/family inheritances so irrationally. I would be so torn.

And…

I think you’re doing the right thing. You’ve memorialized these books with your writing. And better, remembered the forebears who owned and saved these books.

In a memoir of Kyle’s great-great aunt, she talks about how their Arkansas slaves were happy. No one in the last three generations believes that.

I was going to say “Burn the books. Destroy them.” But it’s so hard to say that. 99% of the time. And this is the 1% of the time when it’s a reasoned, moral, valid choice.

Are you a Heather Cox Richardson reader? Something about your brief Juneteenth recap reminded me of this morning’s note.

Sending love,

S

LikeLike

Would donating “The Little Colonel” books. etc. to a museum for preservation be an option for you to consider before burning them? Perhaps, you’ve already considered such action and have decided otherwise; if so, ignore this message. Note: I believe a Black History museum was opened in recent years in Washington D.C. Check it out.

LikeLike

My opinion is not to burn these books. They have too much historical significance.

LikeLike

Ok, I’m back.

Your blog made for some interesting discussion at dinner (which included an eminent theologian & Harvard Divinity School professor- I HAD to throw this in there!), and this led to discussions of erasing history, and the option of putting these books into a library or other historical setting. We talked around some of the many thorny elements of preserving/acknowledging an unwanted/negative history. I’m these are not easy choices.

So, I guess I’m changing my vote (not that I have ANYTHING to do with your decision), to preserving the books.

Sending you love,

S

LikeLike